If you enjoy these Black History stories and want to keep discovering more, consider becoming a subscriber today. Your support helps me share these important narratives with even more people.

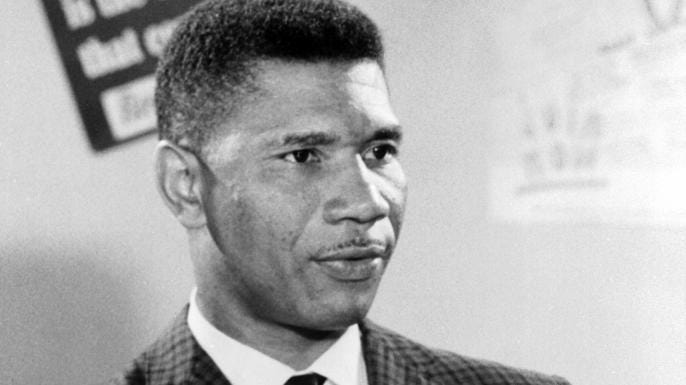

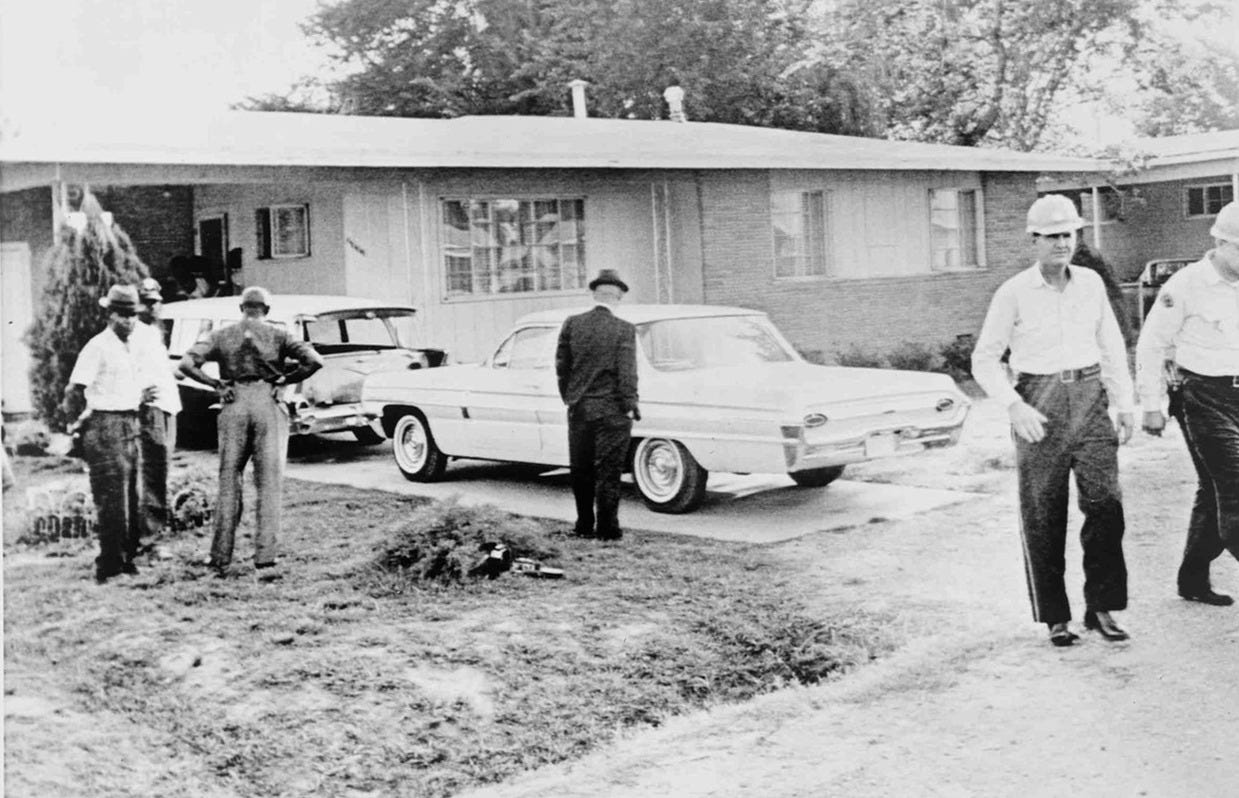

In the early hours of June 12, 1963, Medgar Evers, a relentless force for civil rights, stepped out of his car carrying a set of T-shirts boldly declaring, "Jim Crow Must Go." He had just returned from a meeting with NAACP attorneys, unaware that hatred lurked in the shadows of his Jackson, Mississippi home. As he approached his front door, a single bullet struck him in the back, piercing his heart.

Evers staggered forward 30 feet before collapsing, where his wife, Myrlie, found him moments later. Rushed to the University of Mississippi Medical Center, Evers was shockingly initially denied entry because of his race; only after his family urgently identified him was he admitted. Tragically, he succumbed to his wounds less than an hour later.

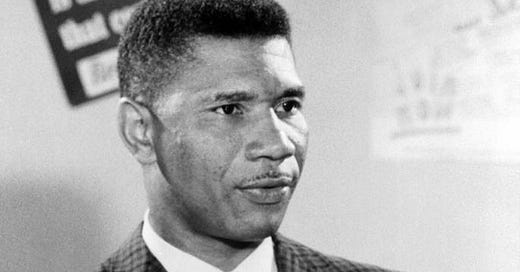

Medgar Wiley Evers, born July 2, 1925, in Decatur, Mississippi, knew hardship early. One of five children to parents Jesse and James Evers, he watched his father labor tirelessly at a sawmill while tending their family's farm. At 18 years old, drafted into the U.S. Army, Evers served bravely across Europe, fighting through the fierce battles in France and Germany, including Normandy in 1944. After returning home in 1946 as a decorated veteran, Medgar turned toward education as a pathway to transform not only his life but also the lives of others, enrolling at Alcorn College in 1948.

At Alcorn, Evers shined but not just as a student, but as an influential and engaged leader: He excelled in debate, sang in the college choir, earned honors as class president, and proved his versatility on the football and track fields. By the time he graduated in 1952 with his Bachelor of Arts in business administration, Evers already knew his purpose lay beyond securing personal success.

Settling in Mound Bayou, Mississippi, Evers took a job selling insurance, yet it wasn't long before activism called him into action. Working closely with the Regional Council of Negro Leadership, he gained his first taste of organized resistance against injustice. Evers orchestrated effective boycotts against businesses that refused basic dignity to African Americans—including gas stations that denied restroom access. The civil rights struggle had found another fierce advocate determined never to back down.

In 1954, following the landmark Supreme Court decision Brown v. Board of Education, Evers and the NAACP cautiously tested Mississippi’s progress toward equality by applying for admission into the racially segregated University of Mississippi Law School—a move swiftly denied. Although his application was rejected, this confrontation elevated Evers' voice within the broader fight for civil rights. Notably guided by attorney Thurgood Marshall, future Supreme Court Justice, Evers’ courage drew the admiration and attention of civil rights leadership nationwide.

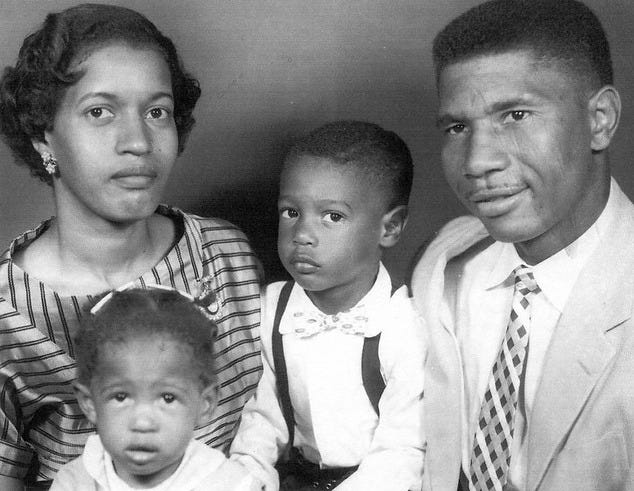

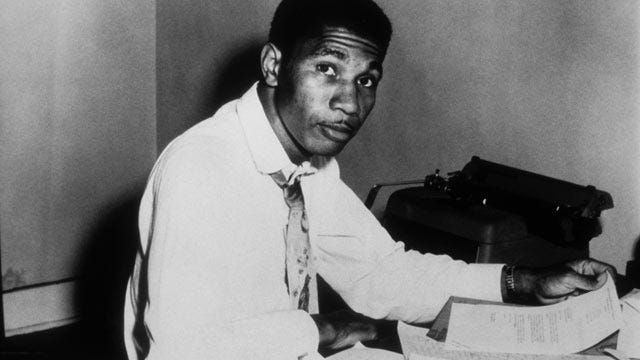

By November 1954, that courage prompted the NAACP to appoint Evers as the very first Mississippi state field secretary. Relocating his young family to Jackson, he plunged headlong into what would become extraordinary activism—fearlessly confronting deep-rooted segregationist practices.

Medgar traveled extensively, tirelessly building the NAACP into a powerful grassroots force across the state. He spearheaded crucial voter registration drives, economic boycotts, peaceful protests, and community chapters of the NAACP. He actively pushed back against the segregation of public spaces— from privately-owned Jackson buses and parks to the segregated public beaches along the Gulf Coast during the Biloxi "wade-ins" across several tense years.

But battling Jim Crow did not come without cost. Evers' commitment to racial justice sparked the fury of white supremacists, making him a constant target. Threats became routine; violence hung heavily in the air. In the tense summer of 1963 alone, he narrowly survived both a Molotov cocktail hurled into his home's carport on May 28, and an attempt to run him down after leaving the Jackson NAACP offices just days later.

Evers lived each moment aware of mortal danger. FBI and local officers often shadowed him, yet, chillingly, on the morning of June 12, those safeguards mysteriously fell away. Arriving home without an escort, he stepped from his car and was swiftly shot in the back. The bullet pierced through him, yet Evers heroically staggered toward his family—finally collapsing at his doorstep. His wife, Myrlie, reached him first, desperately trying to help her fallen husband.

Rushed to the University of Mississippi Medical Center. Evers died less than an hour later at barely 37 years old. His shocking assassination fueled support for sweeping changes that culminated in the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

In death, as he had in life, Evers inspired massive displays of solidarity and defiance. During a procession led by Martin Luther King Jr. and other leaders, over 5,000 individuals marched in Jackson, intentionally defying orders against singing freedom songs. Despite aggressive police intimidation, these courageous mourners carried Medgar’s legacy forward without violence, reaffirming his uncompromising vision of dignity and equality.

Soon after Evers' death, an FBI investigation identified Byron De La Beckwith, known segregationist and founding member of Mississippi's White Citizens' Council, as the prime suspect. Evidence against Beckwith piled high—his fingerprints were found on the murder weapon left near the crime scene, and witnesses placed him nearby that fateful night. Despite this, two separate all-white Mississippi juries, drawn from voter pools that excluding Black citizens, failed to deliver justice, deadlocking in both 1964 trials. Beckwith even received public support from Mississippi's Governor Ross Barnett and walked free after only ten months in jail.

Heartbroken but determined, Myrlie Evers moved her surviving family to California, where she pursued education and never ceased advocating tirelessly for justice. Over twenty-five years passed as the case lay dormant. Then, in 1989, a journalistic investigation reignited public outrage, uncovering troubling details: Mississippi’s state-funded Sovereignty Commission had secretly assisted Beckwith’s legal defense by investigating potential jurors. Armed with these revelations—and driven by Myrlie's unwavering demands for justice a new district attorney reopened the case, locating fresh witnesses willing to speak truth decades after Evers’ murder.

Beckwith was finally arrested again on charges of first-degree murder in December 1990. In January 1994, a mixed-race jury of eight Black and four white jurors listened attentively as witness after witness including former FBI informant Delmar Dennis recounted Beckwith's boasts about assassinating Medgar Evers at Klan events. Beckwith himself appeared frail and worn, listing personal health problems in a desperate effort to garner sympathy. Yet, the evidence proved undeniable.

After almost 31 years, on February 5, 1994, justice finally arrived: Byron De La Beckwith was convicted, sentenced to life in prison without parole. Attempts by Beckwith to appeal the verdict all the way to the Mississippi Supreme Court failed, his conviction upheld at last in 1997. He died in prison on January 21, 2001, at age 80.

Medgar Evers' legacy transcends his tragic end. In death, he became a national symbol of courage against injustice, his story illuminating the brutal racism entrenched in America. His bravery has received ongoing recognition, from the NAACP’s Spingarn Medal in 1963 to President Obama designating his Jackson home as a national historic landmark in 2017. The Medgar and Myrlie Evers Institute, founded by his devoted wife, continues their fight, preserving Evers' powerful vision of racial justice.

In his tragically brief life, Medgar Evers stood firm, calling out racial violence, segregation, and oppression. Though hatred ended his journey prematurely, his spirit lives on in every march, every protest, and every fight against injustice guiding generations still walking in his courageous footsteps.

You can kill a man, but you can't kill an idea

-Medgar Evers

What are you opinions of Medger Evers, We'd love to hear your thoughts and ideas in the comments!

You can learn about more about Black History at my YouTube channel and Podcast