Welcome to our latest blog post on Black History. Today, we delve into the complex history of the One Drop Rule.

Imagine living in a world where even a single drop of ancestry could dictate your entire life. This principle, known as the 'one-drop rule,' is deeply rooted in American history. Its echoes still reverberate today in our perceptions of mixed-race individuals, including notable figures like Barack Obama, Tiger Woods, and Halle Berry.

Langston Hughes noted in his memoir that in the U.S., "Negro" was used to describe anyone with any Black ancestry, whereas in Africa, it referred to someone who was fully Black.

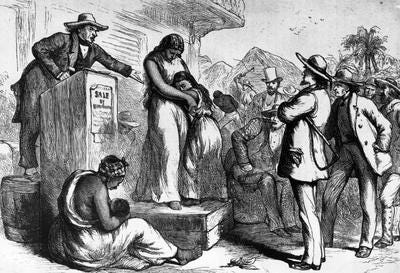

The "one-drop rule" is a social and legal principle of racial classification that was historically prominent in the United States. This rule asserted that any person with even one ancestor of African descent is considered Black, regardless of their physical appearance. The origins and implications of this rule are deeply intertwined with the history of slavery, segregation, and racial dynamics in America.

Dating back to a 1662 Virginia law, this principle laid the groundwork for over three centuries of racial categorization. This law meticulously dictated the social standing of mixed-race individuals. Astonishingly, the echoes of this notion reverberated as recently as 1985 when a Louisiana court clung to its archaic roots and denied a woman’s right to identify as white on her passport, citing a lone Black ancestor from generations past.

One famous historical case involves U.S. President Thomas Jefferson. Based on DNA evidence and historical records, many believe that he had six mixed-race children with his enslaved worker, Sally Hemings. Sally, mostly white and the half-sister of Jefferson’s wife, bore children who, despite their mostly European ancestry, were considered enslaved because their mother was enslaved according to Virginia law at the time.

Jefferson allowed his two oldest children with Sally to quietly escape in 1822. Instead of publicly freeing them, which would have required state permission, he let them go unofficially. In his will, Jefferson formally freed the two youngest children. Three of these four children blended into white society as they grew up, and their descendants also identified as white.

In colonial America, where you fell on the racial spectrum wasn't just about appearance – it determined your very existence. Dark skin, broad noses, and tightly coiled hair were more than physical traits; they were symbols of social inferiority. This crude categorization enforced a brutal hierarchy: white meant freedom, Black often meant enslavement. It was a straightforward, yet deeply insidious delineation that controlled lives and destinies.

However, life is rarely simple. Extensive racial mixing blurred these rigid lines of race and status. Records from as early as 1630 show such anxieties. Colonist Hugh Davis, for instance, was publicly whipped for having sexual relations with a Black woman. Interracial relationships, though rampant, were harshly punished. Any white person caught in such an act faced public humiliation and reprisals.

This mixing posed a significant problem for white supremacy. At a time when Blacks outnumbered whites, there was a palpable fear among whites of losing control over the enslaved population. Therefore, keeping “whiteness” pure became an obsessive goal. White anxieties about racial mixing were tied to ideas like eugenics and scientific racism – both claiming the superiority of the white race and painting Blackness as a contaminant.

To protect this oppressive ideology, it was critical to keep the color line firm and clear. Thus, anti-miscegenation laws were born. These laws made interracial marriage and sometimes even sex a criminal act. Although these laws outwardly appeared to police interactions between different races, they primarily sought to regulate white behavior. While Blacks were already enslaved, these laws ensured that whites adhered to the manufactured boundaries of racial purity.

The impact of these laws went beyond just regulating human relationships; they also shaped legal definitions of race. Many people with mixed ancestry who "looked white" and were mostly of white descent were legally considered white. Different states had varying rules. For example, an 1822 law in Virginia said that to be called mulatto (mixed race), a person needed to have at least one-quarter African ancestry (like one grandparent).

After Nat Turner's Rebellion in 1831, Virginia imposed new rules limiting the freedom of free Black people. However, they didn’t establish the one-drop rule immediately. In 1853, when this rule was suggested, lawmakers realized it could negatively impact many people considered white. Over time, these rules changed. By 1910, Virginia required individuals to have one-sixteenth African ancestry to be considered Black, and by 1930, any African ancestry at all meant a person was legally considered Black.

Contrasting sharply with Virginia's stance on racial definition, New Orleans exhibited a more nuanced approach. In New Orleans, a multi-tiered system emerged, quite distinct from the binary classifications seen elsewhere. Whites held the highest status, Blacks the lowest, and in between, the gens de couleur libre, or Creoles of Color, carved out an intermediate, albeit precarious, social class. These Creoles were a product of generations of intermixing among Europeans, Africans, and Indigenous peoples. Unlike in other regions, interracial relationships were more tolerated—sometimes even encouraged—in colonial Louisiana.

This in-between class, the Creoles, functioned as a buffer, helping whites maintain their dominance and keeping unmixed Blacks firmly in their place. Creole children often received recognition and even freedom from their white fathers. This acknowledgment allowed many Creoles to rise to a position of privilege, becoming an elite class. With this status came a sense of superiority over Blacks, despite many Creoles themselves having African ancestry.

Louisiana developed a caste system based on fractions of Black ancestry. Terms like “Quadroon,” “Octoroon,” and “Griffe” were used to describe the exact proportion of Black and white lineage in a person. This granularity highlights how desperately society clung to racial distinctions, even when those lines were incredibly blurred.

After the Civil War, Southern states created laws to enforce segregation and limit the rights of Black people. These laws, passed from 1890 to 1908, stripped Black people of the right to vote and political participation and remained until the 1960s when federal civil rights laws took effect. A pivotal moment occurred at the South Carolina constitutional convention in 1895, where there was heated debate about whether to include the "one-drop rule." George D. Tillman passionately opposed this, arguing it would wreak havoc on families and lead to endless legal and social complications. Astonishingly, he pointed out that many of the people at the convention likely had mixed ancestry themselves.

The notion of the "one-drop rule" crystallized in the early 20th century. The Supreme Court, in its infamous 1896 Plessy v. Ferguson decision, upheld these segregationist laws by establishing the "separate but equal" doctrine. This ruling, triggered by the case of Homer Plessy—a man classified as Black under Louisiana law due to being one-eighth African—cemented the legal foundation for racial discrimination. Between 1910 and 1930, states like Tennessee, Louisiana, Texas, and Mississippi adopted the "one-drop" rule while other states practiced it de facto. This period, marked by legally enforced racial segregation, extended from the late 19th century well into the mid-20th century, embedding systemic racism deeply into American society.

Fast forward to the 1940s, when individuals like Walter Plecker in Virginia and Naomi Drake in Louisiana took the one-drop rule to draconian extremes, warping records and erasing the rich, diverse heritage of countless families. Plecker’s chilling belief was that the "higher" race must be protected from the "lesser." His actions devastated Native American families in Virginia, stripping them of their heritage in a misguided pursuit of racial purity.

The Racial Integrity Act, passed in Virginia in 1924, prohibited interracial marriage and ushered in a long period of discriminatory racial designation administered by the government. Walter Ashby Plecker, as the head of Virginia’s Bureau of Vital Statistics from 1912-1946, ensured that all infants born in Virginia received birth certificates that included their racial designation. An active eugenicist, Plecker used bureaucracy as a weapon against Black and Indigenous people across the state of Virginia.

Amid this historical tapestry of oppression, there emerged sparks of hope and resilience. The civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s started to dismantle legal segregation, pushing against centuries-old barriers. The landmark 1967 Supreme Court decision in Loving v. Virginia was a watershed moment, striking down Virginia's ban on interracial marriage and unraveling decades of systemic discrimination and erasure of mixed-race identities.

Interestingly, the one-drop rule was unique to the United States and did not find parallels in many other societies with histories of racial mixing, such as in Latin America, where racial identity often acknowledges gradations of ancestry. In Nazi Germany, the Nuremberg Laws devised a system of determining who belonged to what group, allowing the Nazis to criminalize marriage and sex between Jewish and Aryan people. Rather than adopting a “one-drop rule,” the Nazis decreed that a Jewish person was anyone who had three or more Jewish grandparents.

Even today, the remnants of the one-drop rule persist in our societal consciousness. The controversy surrounding Rachel Dolezal triggered national debate about the authenticity of racial identity. The 2000 U.S. Census was a significant milestone, allowing individuals to identify with more than one race for the first time, reflecting a growing recognition of mixed-race identities.

The history of the one-drop rule encapsulates the complexities and contradictions of America's racial history. It is a testament to the ways in which laws and social norms can crystallize racial boundaries that are essentially social constructs. Highlighting this struggle helps us see the ongoing efforts to dismantle these rigid classifications and work toward a more equitable society.

Thank you for joining us today. For more Black stories, visit One Mic History and subscribe to our YouTube channel. Your continued support means the world.

Enjoy our latest episode, and we love you all!

-Countryboi