One Mic Black History Newsletter

Today we tell the stories of the Life of Ota Benga, the Scottsboro Boys and Bloody Sunday.

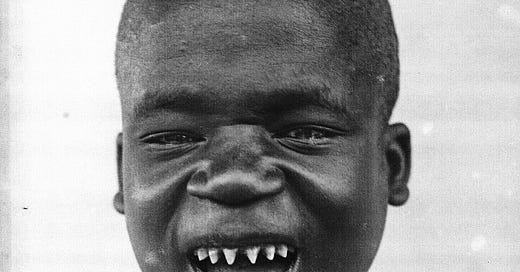

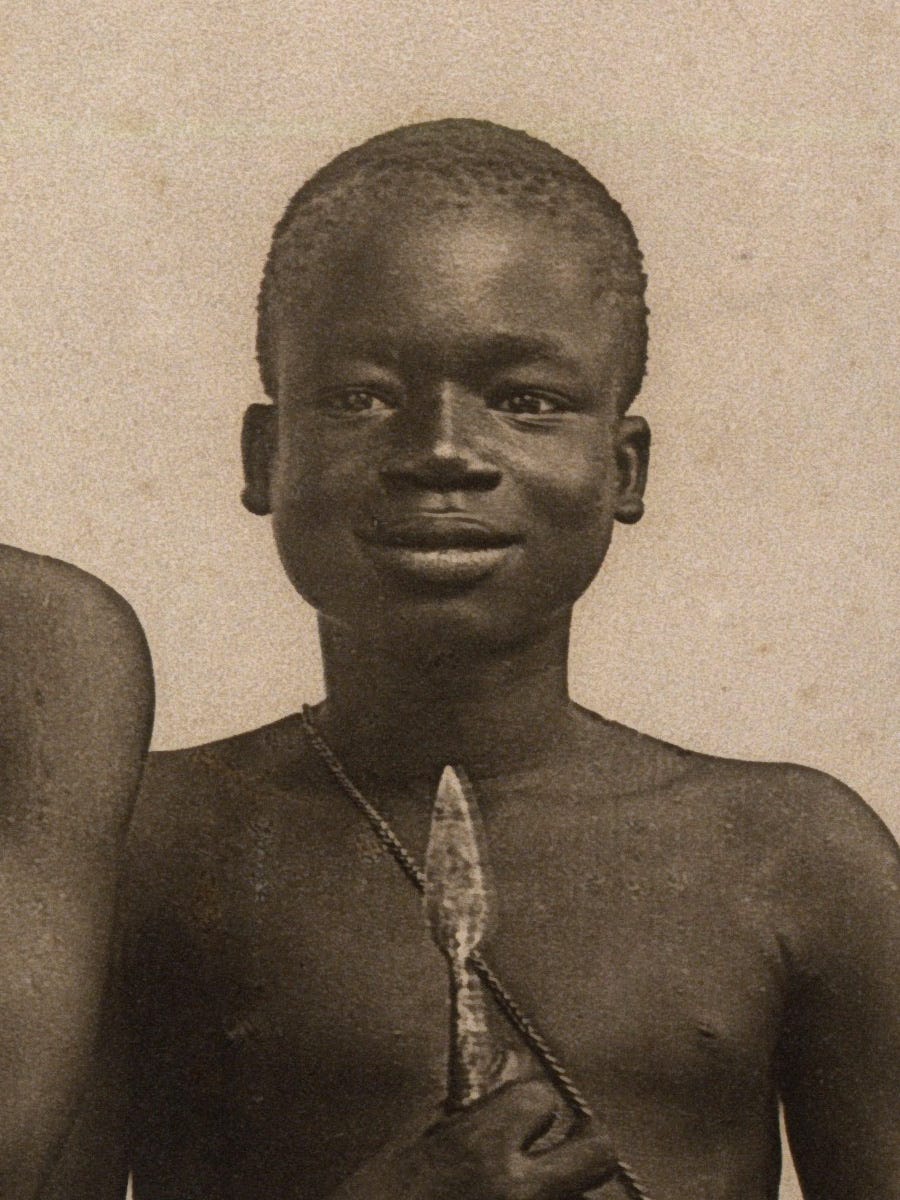

Ota Benga and the Human Zoo

In 1906 the crowds thronged the monkey house exhibit at the Bronx Zoo (New York Zoological Park). Here were man's "evolutionary ancestors" - monkeys, chimpanzees, a gorilla, an orangutan and a African of short stature, named Ota Benga. Ota Benga had been brought to the United States in 1904 by explorer Samuel Verner, and had previously been featured in an exhibit of "pygmies" at the 1904 St. Louis World's Fair.

Ota Benga, was born in 1881 who was only 4 ft. 11in. and weighed 103 lbs., Although he was referred to as a boy he had been married twice. At the time, the Bronx Zoo was under the direction of Dr. William Hornaday, who had eccentric views on animals having nearly human thoughts and personalities. Hornaday placed Ota in a cage in the zoo, claiming it was an “intriguing exhibit”, The exhibit was immensely popular and controversial; the black community was outraged and some churchmen feared that it would convince people of Darwin's theory of evolution. Under threat of legal action, Hornaday had Ota Benga leave his cage and circulate around the zoo in a white suit, but he returned to the monkey house to sleep.

Ota Benga's hated being the object of curiosity. 40,000 visitor a day, crowded the monkey house to see him, shouting and poking him. At one point, he got hold of a knife and brandished it around the park, and another time he made an bow and arrows and started shooting them at the visitors, after this he was able to leave the park. After his park experience, several institutions tried to help him. He was placed in Virginia Theological Seminary and College but quit school to work in a tobacco factory. He soon grew homesick, hostile, and despondent, then he borrowed a revolver, and shot himself in the heart, killed himself in 1916.

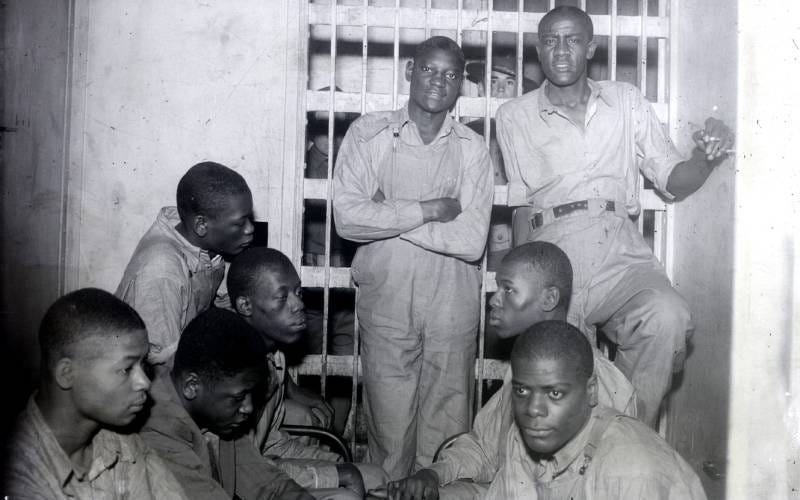

The Scottsboro Boys

On March 25, 1931, nine Black teenagers riding a freight train through Alabama and north toward Memphis, Tennessee, were arrested after being falsely accused of raping two white women. After nearly being lynched, they were brought to trial in Scottsboro, Alabama.

Despite evidence that exonerated the teens, including a retraction by Ruby Bates on of their accusers, the state pursued the case. All-white juries delivered guilty verdicts and all nine defendants, except the youngest, were sentenced to death. In 1932, the U.S. Supreme Court concluded in Powell v. Alabama that the Scottsboro defendants had been denied adequate counsel at trial. In 1935, in Norris v. Alabama, the Court again ruled in favor of the defendants, overturning their convictions because Alabama had systematically excluded Black people from jury service.

From 1931 to 1937, during a series of appeals and new trials, they languished in Alabama's Kilby prison, Finally, four of the defendants were released and five were given sentences from 20 years to life; four of the defendants sentenced to prison time were released on parole between 1943 and 1950, while the fifth escaped prison in 1948 and fled to Michigan. One of the Scottsboro Boys, Clarence Norris, walked out of Kilby Prison in 1946 after being paroled; he moved North to make a life for himself and did not receive a full pardon until 30 years later.

Their trials and retrials of the Scottsboro Boys sparked an international uproar and produced two landmark U.S. Supreme Court verdicts, this represented the first time in Alabama that a black man had not been sentenced to death in the rape of a white woman.

Learn more about the Scottsboro Boys:

Bloody Sunday

"On a day that would come to be known as Bloody Sunday, the peaceful march of the civil rights activists in Selma to Montgomery Alabama was met with a violent and from Alabama state troopers

no place in the nation had a tighter grip on Jim Crow than in Dallas County, Alabama, where African Americans made up more than half of the population, yet accounted for just 2 percent of registered voters. In January 1965, Martin Luther King, Jr., came to the city to make Selma’s inflexibly to black voting rights a national concern. SCLC hoped to gather moment federal protection for a voting rights statute but even peaceful demonstrations in Selma and surrounding communities resulted in the arrests of thousands of Protestors.

On February 18, protester Jimmy Lee Jackson was shot by an Alabama state trooper and died eight days later. In response, civil rights leaders planned to take their cause directly to Alabama Governor George Wallace on a 54-mile march from Selma to the state capital of Montgomery. Although Wallace ordered state troopers “to use whatever measures are necessary to prevent a march,” still approximately 600 voting rights advocates set out from the Brown Chapel AME Church on Sunday, March 7.

John Lewis and other activists from the SNCC and SCLC began the marched from Selma, Alabama, to Montgomery, When they arrived at the Edmund Pettus Bridge, they were met by police and state troopers wearing white helmets and armed with billy clubs. The officers demanded that the protesters turn around, but when they refused, the officers used tear gas and physically attacked the peaceful demonstrators. As a result, over fifty people were wounded and required medical attention.

That evening, ABC News interrupted the airing of "Judgment at Nuremberg", a movie that examines Nazi war crimes and the moral responsibility of those who followed orders without speaking out against the Holocaust, to broadcast the horrifying footage of the violence from Selma. Approximately 50 million Americans, who had been eagerly awaiting the film's television debut, were confronted with shocking images and helping to rouse support for the civil rights cause

Two days after the first march, Martin Luther King asked civil rights supporters to come to Selma for a second march. Members of Congress suggested that the march be delayed until a court could decide if the protesters deserved federal protection, and King was uncertain whether to wait or not. He eventually decided to lead the second protest on March 9, but the march ended before reaching the Edmund Pettus Bridge due to the presence of Alabama state troops.

Later on March 21, a final successful march began with federal protection, and The events in Selma galvanized public opinion and mobilized Congress to pass the Voting Rights Act, which President Johnson signed into law on August 6, 1965.

Podcast Episode

S5E3: Why Don’t Black Folks eat Pumpkin Pie?

Why Don't Black Folks eat Pumpkin Pie? How did we start eating Sweet Potato Pie? Join us while we detail the answer to these puzzling questions.

Listen, enjoy and we will give the answers to both these burning questions at Onemichistory.com

Thank you so much for joining us today, I hope you have a wonderful day, If you like stories like this you can find more stories like this at One Mic History. Monday 3/27, we have a new episode; S5E7 How Did Watermelons Became Racist?

Thank you and I appreciate your support.

-Countryboi