One Mic Black History Newsletter

Today we tell the stories of the Birthdays of Ida B. Wells, Dred Scott and The Arkansas Negro Boys Industrial School

Good Day, Fam, Welcome Back to One Mic History Newsletter. Thank you for joining us today. I appreciate you. If you enjoy stories like this you can find more stories like this on One Mic History. You can also join us on Instagram, TikTok and YouTube at One Mic History.

Dred Scott v. Sandford

On March 6, 1857, in Dred Scott v. Sandford, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that Black people were not American citizens and could not sue in courts of law. The Court ruled against Dred Scott, an enslaved Black man who tried to sue for his freedom.

For years before this case began, Dred Scott was enslaved by Dr. John Emerson, a military physician who traveled and resided in several states and territories where slavery was illegal—always accompanied by Dred Scott. Dr. Emerson eventually took Mr. Scott back to Missouri, where slavery was legal. When Dr. Emerson died there in 1843, Mr. Scott was still enslaved.

After Dr. Emerson's death, Dred Scott and his wife, Harriet, sought freedom in the Missouri state courts. The Scotts argued that their prior residence in free territories had voided their enslavement. The Missouri Supreme Court ruled against the Scotts and authorized Dr. Emerson's widow, Irene, to continue to enslave them. When Irene Emerson later gave her estate, including the Scotts, to her brother, John Sandford, Dred Scott brought suit in federal court.

March 1857, Dred Scott found he lost his fight for freedom once again. The Supreme Court's Dred Scott decision held that the 5th Amendment did not allow the federal government to deprive a citizen of property, including enslaved people, without due process of law. He also wrote "All men are created Equal" except people of African descent, free or enslaved, because they were not United States citizens and subsequently had no right to sue in federal court.

This ruling kept the Scotts legally enslaved, invalidated the Missouri Compromise, and re-opened the question of slavery's expansion into the territories. The resulting legal uncertainty greatly increased sectional tensions between Northern and Southern states and pushed the nation forward on the path toward civil war.

Unable to win liberty in the courts, Dred and Harriet Scott were freed by a subsequent enslaver a few months after the decision. Dred Scott died just months later of tuberculosis, while Harriet Scott lived until 1876.

Tiktok failed to load.

Tiktok failed to load.Enable 3rd party cookies or use another browser

Tragedy in Wrightville

On March 5, 1959, 21 Black teenagers died in a building fire after being left alone and locked inside of their dormitory at a neglected and segregated “reform” school in Arkansas.

The Negro Boys Industrial School (NBIS) was a juvenile work farm located in the vicinity of Wrightsville, most of the boys, aged between 13 and 17, had either been orphaned, homeless, or were considered delinquents due to their involvement in minor offenses. According to L. R. Gaines superintendent of the reform school "most of the boys in the dormitory were in for minor offenses such as hubcap stealing, or because their parents had split and there was no place for them to go."

The teenagers at NBIS were exposed to dangerous conditions even long-standing prior to the fire. In 1956, a sociologist Gordon Morgan visited the site and reported alarming details regarding the students' living environment. “Many boys go for days with only rags for clothes. More than half of them wear neither socks nor underwear during [the winter] of 1955–56….[It is] not uncommon to see youths going for weeks without bathing or changing clothes.” At times, the number of boys at the “school” was over 100. There was no laundry equipment. A single thirty-gallon hot water tank served the bathing needs of the entire population. The water was deemed so undrinkable that even Employees brought their own drinking water to work.

Additionally “All buildings…are in need of extensive repairs, particularly the boys’ living quarters,” As NBIS was supposed to be as self-sustaining an operation as possible, the emphasis was on farm yields but maintenance was in short supply or non-existent.

In the early hours of March 5, 1959, staff members of the NBIS Boys' Dormitory had left the facility for the night, leaving it completely unsupervised. Around this time, 16-year-old Arthur Ray Poole, one of two inmate "sergeants," detected smoke emanating from the building. The doors had been locked and the windows secured with heavy gauge wire mesh, making escape difficult. However, 48 of the African American teenagers were able to free themselves from the flames by leaping out of the windows. Unfortunately, 21 teenagers remained trapped and perished in the fire.

The police did not conduct an investigation in order to identify the source of the fire, however, it was speculated that the deteriorating conditions could have been the cause. Subsequently, Governor Orval Faubus acknowledged that the wiring may have played a part in the incident. The Pulaski County Grand Jury asserted that numerous individuals and agencies were accountable, but they reached no criminal verdicts.

The families of the deceased reported that they were informed by authorities that 14 of the boys had been wrapped in newspapers and laid to rest in an unmarked grave at Haven of Rest Cemetery in Little Rock, Arkansas. The gravesite remained unmarked until 2018, when a plaque memorializing the boys was donated to the site.

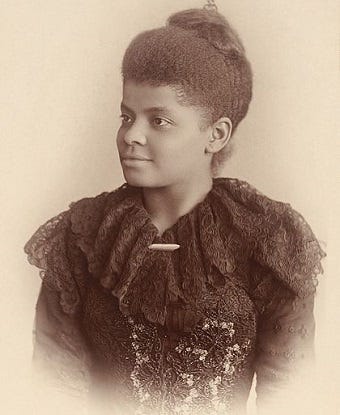

Ida B Wells Vs The World

During this Women's History Month, I want to talk about one of my heroes, Ida B. Wells. She was a journalist, abolitionist and feminist, who led an anti-lynching crusade in the United States in the 1890s.

During this 1890s, lynching was solidified as a terrorist campaign for white control of the South. Most often the victims were Black men accused of raping white women. Ida doubted this and explained that often the charge was made after a man had been hanged or burned or shot. She thought it more likely that victims had been in a consensual relationship with a white woman or, like her friend Thomas Moss, were businessmen who threatened rival whites and had no connection to white women at all.

Ida wrote a series of anti-lynching editorials in the Free Speech newspaper. Ida stated

"that old threadbare lie that Negro men rape White women. If Southern men are not careful, a conclusion might be reached which will be very damaging to the moral reputation of their women."

This editorial seemed to push some of the Memphis' white southerners over the edge. Afterwards a mob ransacked the Free Speech office in Memphis, destroying the building and its contents, Luckily, Wells had been traveling to New York City. The mob continued to watch the train station for her return. Creditors took possession of the office and sold the remaining assets of Free Speech. It was clear made she could not return to Memphis. Wells subsequently accepted a job with New York Age and continued her anti lynching campaign, from then on she lived in the North, mostly in Chicago, and changed her pen name to “Exiled.

In October of 1892, Ida B. Wells published "Southern Horrors: Lynch Law in All Its Phases" which contained her research on lynchings. She found that many lynchings in the South were attributed to the alleged "rape of White women". Following in-depth research on the prevalence of lynching in 1895, Wells released The Red Record, a 100-page pamphlet that detailed lynching in the United States since the Emancipation Proclamation of 1863.

This publication focused on the alarming rise in lynching from 1880 to 1930, She believed that during the time of slavery, fewer cases of violence against Black people occurred due to the economic value of slaves. After the Civil War, White people felt threatened by African Americans and attempted to oppress them through violent means. These attacks were meant to maintain White supremacy and keep Black people from voting or taking office.

These works led Wells concluded that armed resistance was the only defense against lynching.

Podcast Episode

S5E6: Why do Black People love Hennessy?

Why Do Black Folks love Cognac? Have you ever wondered why Hennessy has a stranglehold on the Black community or how Woke became a curse word?

Listen, enjoy and we will give the answers to both these burning questions at Onemichistory.com.

Thank you so much for joining us today, I hope you have a wonderful day, If you like stories like this you can find more stories like this at One Mic History.

Thank you and I appreciate your support.

-Countryboi