Good Day Fam, Welcome Back to One Mic History Newsletter. Thank you for joining us today, I appreciate your support. Today we have something special for the holidays: The history of Black Folks and Christmas.

Christmas, recognized as a celebration of the birth of the Christian figure, Jesus Christ, has, over a span of two millennia, metamorphosed into a globally observed holiday that harmoniously adapts and shades Christian and secular customs into distinctive celebrations, conditioned by regional cultures and individual convictions.

For those of African descent who lived under the burden of slavery, the significance of Christmas was two fold. First, it signified a brief period of relative ease and relaxation from the demands of slavery, even if just for a few days. Secondly, it represented a period of deep spiritual contemplation and expression, largely influenced by Christianity, delivered to them by both missionaries and their slave masters.

In the 1830s, the Southern slaveholding states of Alabama, Louisiana, and Arkansas became the first regions in the United States to declare Christmas a state holiday. Throughout the antebellum era, Christmas traditions such as exchanging gifts, singing carols, and decorating homes were strongly institutionalized in American culture. For the enslaved workforce, Christmas generally granted the longest holiday of the year, with the better-off among them even granted the privilege of family visits or marriages. It was common for slaves to receive gifts from their owners and indulge in exceptional festive foods that were otherwise inaccessible throughout the year.

The Christmas season offered the enslaved a temporary hiatus from their laborious work schedules. Many slaves were given a few days off during the season, allowing them to participate in activities ordinarily impossible during the rest of the year such as visiting friends on neighboring plantations, hunting, and fishing for additional food, or simply congregating socially in the spirit of song, dance, and storytelling.

Abolitionist Frederick Douglass "This time we regarded as our own, by the grace of our masters; and we, therefore, used or abused it nearly as we pleased,"

Some of the enslaved would use the relaxed holiday period was the fact that some enslaved individuals seized the opportunity to chart their route to freedom. In 1848, Ellen and William Craft, a slave couple from Macon, Georgia, masterfully used travel passes from their slave masters, which were granted in the Christmas spirit, to orchestrate an elaborate escape by train and steamer to Philadelphia. Harriet Tubman, helped her brothers escape at Christmas. Their master intended to sell them after Christmas but was delayed by the holiday. The brothers were expected to spend the day with their elderly mother but met Tubman in secret. She helped them travel north, gaining a head start on the master who did not discover their disappearance until the end of the holidays.

Christmas could represent not only physical freedom, but spiritual freedom with the hope for better days ahead. The main character of Martha Griffin Browne's “Autobiography of a Female Slave” was a slave named Ann, she found hope in the story of Jesus Christ that symbolized Christmas for her. Even as she rejected the masters' interpretation of Christmas, equating it with strengthened bonds of servitude, she found solace and promises of freedom in the life of Jesus Christ.

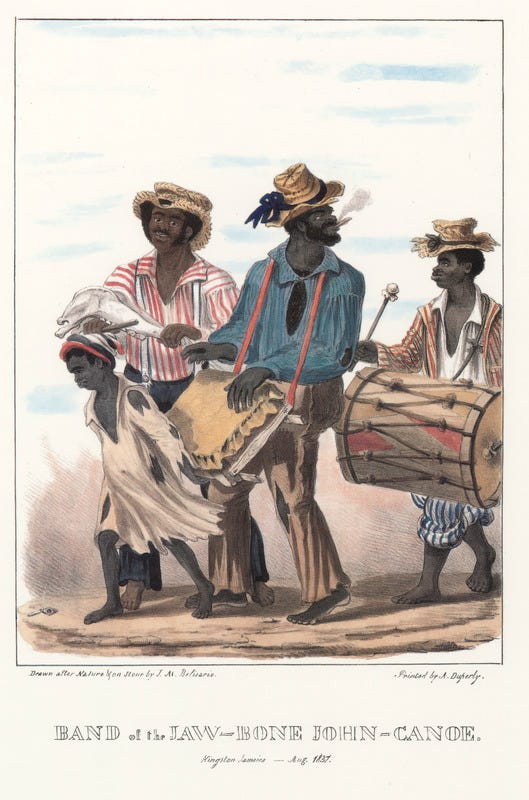

During these celebrations, elements of their African roots merged with the newly introduced Christian narratives surrounding Christmas. They adapted the Christmas customs and symbols of their European enslavers to reflect their own interpretations as they melded their cultural practices into them. For many, Christmas was identifiable with the celebration of Jonkonnu, an African cultural festival involving music, dancing and masquerading.

In Wilmington, North Carolina, for instance, enslaved people celebrated 'John Kunering' (also known as Jonkonnu, John Kannaus, John Canoe), in which they adorned themselves in fantastical costumes and moved from house to house expressing joy through singing, dancing, and rhythmic performances.

The practice of gift-giving among slaveholders during Christmas embodied a continuous reinforcement of their dominance towards enslaved individuals. The enslaved languishing under economic disparities that impeded their ability to purchase gifts. It was common for the slave owners, during the holiday season, to present their enslaved workers with commodities such as clothes, shoes, or money – things they usually denied them throughout the year.

Texas Historian, Elizabeth Silverthorne, cites an example of a slaveholder who gifted each of his enslaved families $25. Furthermore, the children were provided with candy-filled sacks and pennies. Recounting the joy of enslaved workers receiving these gifts, a Southern planter spoke about their observation of the pleased reactions of the enslaved filled with grins, smiles, and bows.

In his book, “The Battle for Christmas” Stephen Nissenbaum narrates an incident where a white overseer found the act of Christmas gift-giving to be more effective in exercising control over the enslaved individuals than resorting to physical violence. The overseer stated “I killed twenty-eight head of beef for the people’s Christmas dinner,” he said. “I can do more with them in this way than if all the hides of the cattle were made into lashes.”

Enslaved people rarely made reciprocal gifts to their owners, historians Shauna Bigham and Robert E. May: “Fleeting displays of economic equality would have controverted the [enslaved workers] prescribed role of childlike dependency.” Even when they played a common holiday game with their owners—where the first person who could surprise the other by saying “Christmas Gift!” received a present—they were not expected to give gifts when they lost.

There were exceptional cases where enslaved workers returned gifts to their masters during the customary holiday game. For instance, a report that on a certain plantation in South Carolina, some enslaved house workers offered their owners eggs, carefully wrapped in handkerchiefs. However, such instances were rare. The general trend of one-sided gift-giving from slaveholders served to entrench the dynamics of white supremacy and paternalism.

After Emancipation and moving in to the Reconstruction period in the late 1860s ushered in freedom for enslaved Africans, it also substantially altered the landscape of Christmas celebrations among African Americans in the Southern United States. For the first time, African Americans were able to imbue the holiday with cultural traditions from their African ancestry. However, the their socio-economic plight and rampant racial discrimination continued to make Christmas largely a period of introspection and resilience for the newly-freed Africans.

From the shadows of slavery and segregation, Christmas traditions transformed to incorporate values of spirituality, community, equality, and ancestral reminiscence. Gospel choirs, spiritual hymns, and jazz performances became the mainstay of black Christmas celebrations, providing a unique soundtrack to the festivities. Culinary traditions, too, served as distinct identifiers for the African American Christmas, with dishes such as collard greens, black-eyed peas, and cornbread combining Southern and African influences, a testament to a lineage handed down across generations.

During the period of the Great Migration, where African Americans migrated en mass to the urban North, had considerable impact on the Christmas customs. Suffused with newfound urban prosperity, black Christmas celebrations expanded to include material gifts and decorations reflective of mainstream American customs. Such ostentation served both as a demonstration of upward mobility as well as a consolidation of the cultural characteristics unique to the African American community.

Early 20th-century sociocultural context heralded the conception of a Black Santa Claus, Originating from a desire to represent the festive season in a way that reflects the multiethnic reality of society, Black Santa has emerged as a cultural emblem among the African American community. He is not merely a mythological figure; he represents the breaking of racial barriers, a symbol of hope, inclusivity, and diversity. For black children, Black Santa is an affirmation of their identity, meaning, and place in society.

The Black Church has played a crucial role in shaping Black Christmas traditions, offering spiritual comfort and a sense of community in the face of discrimination. Essential to these traditions are events like candle services, church plays, and the singing of spirituals and hymns, which have become defining characteristics of African American Christmas celebrations. Even today, A recent study by the Pew Research Center in 2019 found that approximately 79% of African Americans are more inclined to attend church services on either Christmas Eve or Christmas Day.

An essential part of the African American Christmas experience is the black church's role. The church, for centuries, has served as a haven and institution of liberation for the black community. Historically, Christmas in the black community is associated with Watch Night services and nativity plays recalling the birth of Jesus Christ. Christmas carols composed and sung by African Americans like "Go Tell It on the Mountain" and "Sweet Little Jesus Boy" tend to highlight the human aspect of Jesus and his humble birth.

Fast forwarding to the mid-twentieth century, the Civil Rights Movement brought renewed hope for equal rights and societal acceptance. Christmas during this period took on a more profound meaning for black folks. The holiday period was often utilized as a platform to rally support and highlight racial injustice.

One instance of this is the Christmas boycott of 1960 in Greenville, North Carolina. Where black leaders successfully organized a citywide boycott of white-owned businesses to protest racial segregation. The boycott hit the merchants at their busiest time of the year, thereby severely singing their profits. Activists believed that this kind of economic impact could push the conversation around desegregation forward.

Unsurprisingly, the spirit of Christmas was also reflected in several speeches and writing. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., resonated with the virtues of peace, love, and goodwill encapsulated by Christmas. He used the occasion to reinforce and promote the movement's objectives effectively.

In essence, Christmas in African American history has been a reflection of the times, speaking to the prevailing societal conditions and the state of civil liberties. From the first free Christmas celebrations during the Reconstruction era to its strategic use during the Civil Rights Movement, Christmas played a crucial role in African American history. It allowed them to forge unique traditions, unite communities during tough times, and push for civil rights.

Today, Christmas represents a time of family, love, and reflection for many African Americans. As Maya Angelou notes that, “The ache for home lives in all of us, the safe place where we can go as we are and not be questioned.” Christmas seems to symbolically embrace this quote and offer a season where black folks can be themselves, reconnect with their roots, and celebrate this special time without being questioned.

The celebration of Christmas today is in many ways influenced by a unique mix of religious devotion, cultural pride, and family bonds. I personally recall Sundays leading to Christmas filled with sermons emphasizing on love, hope, and faith. The Christmas Eve service, filled with prayer, song, and community love. The narrative of Jesus' birth was also cleverly interwoven with current issues, symbolically reminding us that despite present adversities, the hope for redemption and change always exists.

Thank you so much for joining us today, I hope you have a wonderful day, If you like stories like this you can find more stories like this at One Mic History.

Thank you, I appreciate your support and Happy Holidays

-Countryboi