If you enjoy these Black History stories and want to keep discovering more, consider becoming a subscriber today. Your support helps me share these important narratives with even more people.

Dick Rowland was a young and charismatic 19-year-old African American living in Tulsa, Oklahoma in 1921. He earned a reputation shining shoes at a local pool hall on Third and Main, a simple job that could earn him as much as $10 a day, a significant sum at a time when a shoe shine cost just ten cents. Known for his sharp suits, diamond ring, and engaging personality, Rowland was one of many Black men who represented optimism within Tulsa's prosperous Greenwood district, known nationally as "Black Wall Street."

On Memorial Day, May 30th, 1921 Rowland headed to the Drexel Building in downtown Tulsa. The building housed a rare "colored" only restroom on its upper floor. As Rowland entered the elevator operated by a white 17-year-old named Sarah Page, a series of events unfolded that forever altering Tulsa’s history.

Although reports differ greatly, the most reliable account suggests Rowland tripped upon entering the elevator and instinctively grabbed Sarah's arm for balance. Sarah's scream startled witnesses nearby, and a white store clerk saw Rowland leave the elevator in panic. Despite varying testimonies, what followed a familiar pattern of racial fear and accusation.

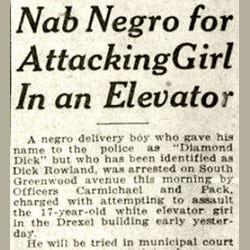

The local newspaper, the Tulsa Tribune, ignited the already volatile situation with an explosive headline, "Nab Negro for Attacking Girl in Elevator!" Although Sarah Page herself would later clarify that no attack occurred, the Tribune had carelessly triggered dangerous stereotypes and fears. Speculation of an imminent lynching spread across the white community, igniting a panic.

The Spark Before an Explosion

Local African American residents remembered vividly that just eight months earlier, a white mob had lynched another man named Roy Belton from the county jail. Greenwood's Black community decided this wouldn’t happen again, mobilizing to defend one of their own.

Members of Greenwood gathered to protect Dick Rowland and prevent another lynching. O.W. Gurley, a respected community leader, urged peace and patience after assurances from Tulsa Sheriff Willard McCullough that Rowland would be safe. But the younger more militant voices dismissed these promises. Community frustration continued to grow.

how many times had white authorities assured safety only to permit a brutal lynching?

At 9:15 pm, twenty-five armed Black Tulsans arrived to offer protection at the courthouse. Though Sheriff McCullough assured them of Rowland's safety, tension thickened. Later that night, another larger group returned after hearing rumored plots to storm the jail and lynch Rowland. As confrontations intensified outside the courthouse, heated words transitioned into physical struggle. In this tense moment, a shot rang out, unleashing chaos on the Tulsa Streets.

In mere seconds, confusion exploded into bloodshed, prompting a full-scale retreat toward Greenwood amidst gunfire. White mobs, enraged by resistance from the Black community, regrouped and armed themselves heavily, looting weapons and valuables from downtown stores.

The stage was set for tragedy.

Despite the appearance of restoring order, Tulsa police deputies openly assisted white rioters, legitimizing mob violence. Armed deputized white civilians patrolled the streets, while law enforcement either explicitly supported or tacitly permitted the violence against the Greenwood district.

Just after midnight, white mobs invaded Greenwood. They strategically ignited fires by throwing incendiary devices into wooden Black homes and businesses. Wind quickly spread flames throughout the community. Firefighters responding to emergencies faced threats from armed whites and withdrew, leaving the fires to consume homes without intervention. Power and telephone lines were deliberately destroyed, isolating Greenwood residents from any outside aid.

Governor James Robertson hesitated to act, trusting local authorities who falsely claimed control over the situation. Only early on June 1st did a few National Guard forces arrive, overwhelmed by the magnitude of violence. Yet rather than restore peace, guardsmen themselves engaged in fierce gun battles against small groups of Black defenders, mistaking survival for rebellion.

Meanwhile, planes flew overhead. Though officially dismissed as merely reconnaissance missions, survivors vividly remembered aircraft dropping flaming projectiles onto buildings and terrorizing residents fleeing below, a harrowing, unprecedented aerial assault on an American city and its people.

Black residents fled their homes in despair. Terrified families ran barefoot through the burning streets, seeking refuge miles away. For others, escape was impossible.

Men, women, and children were violently marched through Tulsa’s downtown streets to makeshift detainment centers at the fairgrounds. Onlookers treated the humiliation as spectacle; businesses granted employees days off to witness "the event."

Amidst the chaos, even peaceful surrender provided no guarantee of survival. Black surgeon Dr. A.C Jackson attempted to surrender with hands raised, only to be shot in cold blood. His home burned behind him, the destruction serving as a grim reminder of unchecked hatred.

In the Aftermath

Ironically, Dick Rowland himself survived untouched, secretly removed from Tulsa the morning after violence erupted. Yet Greenwood suffered immensely: 35 city blocks burned to ash; nearly 200 African American businesses destroyed; 1,256 homes left in ruins; hundreds of lives distorted by violence; survivors imprisoned, displaced, and traumatized.

Despite overwhelming evidence of guilt, white Tulsa never faced real accountability. Insurance companies used loopholes to deny restitution claims. Courts continuously sided against survivors seeking justice. For decades, powerful interests silenced discussions, removing incriminating documents and sanitizing newspapers to erase the event from public memory entirely.

Until very recently, the story of the Tulsa Race Massacre remained deliberately buried. It was omitted from schoolbooks, archives, and collective memory. Survivors' voices were overshadowed by intentional silence until community organizations and historians slowly unearthed the horrible truth.

In 1996, hope stirred in Oklahoma as a state commission officially recognized the horrific truths behind the Tulsa Race Massacre. After decades of silence and erasure, this commission recommended meaningful reparations over $33 million to be awarded by the state legislature to 121 verified survivors and their descendants. Yet, despite the glaring evidence, despite the magnitude of harm, these powerful calls for justice went unanswered, ignored by state legislators who chose inertia over action.

Instead, in 2002, survivors received what could only be described as a token gesture: Tulsa Metropolitan Ministry, a private charity, extended a total of just $28,000 in reparations, less than $200 per survivor. The injustice persisted, and frustration simmered.

This led to Tulsa Attorney Damario Solomon-Simmons, a Black attorney based in Tulsa, who picked up Oklahoma’s public nuisance law as a creative weapon for real accountability. Solomon-Simmons and his fellow advocates boldly argued that the violent destruction and ongoing neglect following the massacre created lasting, systemic harm demanding remedy.

Yet even this effort has faced fierce resistance. The Oklahoma Supreme Court dismissed one lawsuit seeking reparations, pouring fresh salt into Tulsa’s lasting wounds and fueling righteous anger within the Black community and beyond.

Justice delayed became justice denied—again.

However, the truth buried beneath decades of silence refused to stay hidden. In 2020, after nearly a century of official denial and collective forgetting, archaeologists unearthed mass graves believed linked to the massacre. Those chilling discoveries provided a haunting validation of the survivors' testimonies. A tragic testament to the violence committed, and compelling evidence that Tulsa's history could never be buried forever.

Conclusion

Dick Rowland, set off a devastating chain reaction that would forever scar the history of Greenwood. Rowland's seemingly minor interaction sparked hidden tensions lying just beneath the city's surface, unleashing racial resentment, white supremacy, and an unchecked wave of violence that decimated Greenwood, otherwise known as Black Wall Street.

The Tulsa Race Massacre remains, to this day, a disturbing symbol of what happens when hatred and prejudice are allowed to fester without confrontation or accountability. The painful memories of that horrific incident remind us of the heavy costs borne by communities when racism is left unchecked.

In the decades following the tragedy, Tulsa's Black community and their descendants have tirelessly pursued justice not simple in the form of monetary reparations, but as a shared recognition of pain and loss, a necessary affirmation of human dignity, and a long-overdue step toward healing.

Today, activists, survivors, and local advocates continue to preserve the memory of Greenwood, confronting America with its difficult past and demanding a genuine reckoning. Efforts toward commemoration, mandatory education on these events, and historical investigations into the tragedy mark significant, albeit slow, progress toward reconciliation.

Yet, we must continually ask ourselves as Americans: How do we truly reckon with the dark chapters of our past? Only by genuinely addressing these wounds, and by keeping the story of Greenwood alive.

Can we ensure that the horrors of Tulsa Massacre never happen again.

What are you opinions of Tulsa Massacre, We'd love to hear your thoughts and ideas in the comments.

You can learn about more about Black History at my YouTube channel and Podcast

Thank you for your work!

This is a great post. I grew up in Tulsa, graduated school in 2007. I was never taught about the race massacre in Oklahoma history. I only knew about it because my dad would drive me around town as a kid and he would show me the mass graves and discuss what happened. When I was a teenager and got my first car, I would drive my friends around town and when we were in that area I would tell them about it. Currently we live on old black farm land that used to be known as "Rentie Grove", if you haven't looked into it-check it out. There is still a cemetery in the neighborhood.