Welcome to One Mic History Newsletter. Thank you for your continued support. Today, we delve into a fascinating story of Thomas Jefferson’s enslaved personal chef James Hemings.

Late in the 18th century, at Monticello, the sprawling estate of Thomas Jefferson, life was marked by contradictions—liberty and slavery, innovation and oppression. Jefferson, known widely as a Founding Father and champion of freedom, at the peak of his prominence held more than 600 individuals in slavery, with over 140 enslaved men, women, and children forced to labor on his land. Among them was an extraordinary family whose legacy demands attention: the Hemings family.

James Hemings was born into the harsh realities of slavery in 1765, brought into Jefferson's sphere through his mother's connection to Jefferson's father-in-law, John Wayles. In a cruel twist of fate, James' position as Jefferson’s slave was complicated by family ties: after Jefferson married Martha Wayles Skelton in 1772, James became both his brother-in-law and his property. Even in such circumstances, James showed remarkable talent and intelligence, learning to read at a time when literacy among enslaved individuals was fiercely restricted.

Recognizing James's potential, Jefferson decided to cultivate his rare skills, laying the groundwork for Hemings to become a pioneering chef whose brilliance shaped the very essence of American cuisine. At just 19 years old, James and his younger sister Sally Hemings crossed the Atlantic alongside Jefferson, headed for Paris after Jefferson's appointment as minister to France. There, James underwent rigorous culinary training with acclaimed chefs at the Château de Chantilly. Rapidly honing his skills, he soon mastered the blend of classical French techniques and distinctly American flavors, becoming head chef at Jefferson’s Paris residence, Hôtel de Langeac.

In Paris, James could have pursued liberties far beyond his wildest dreams—France had laws allowing enslaved people to petition for their freedom. Yet, driven by fears of permanently separating from family members left behind in America, both James and Sally chose to return with Jefferson, surrendering possible freedom for the hope of unity.

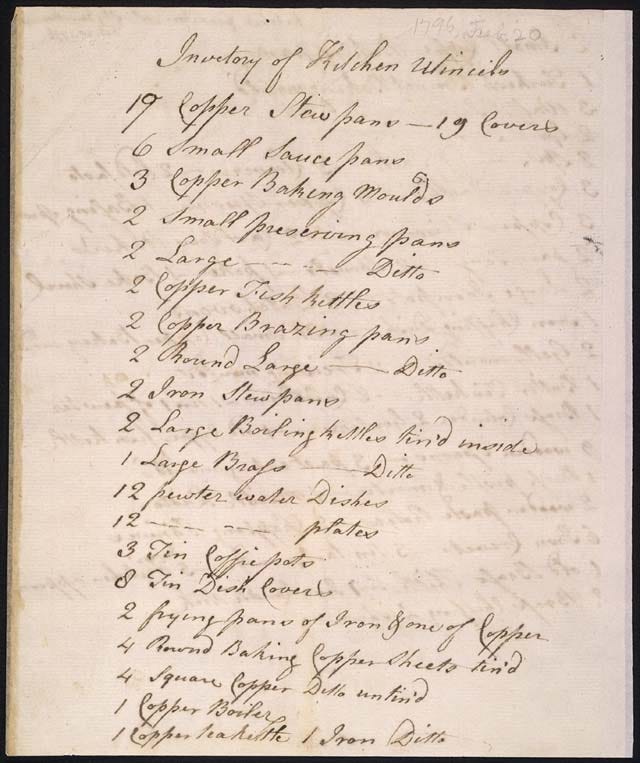

Upon returning to America, James Hemings continued to showcase his unmatched culinary talents inside Jefferson’s kitchens, achieving a degree of recognition rare among enslaved individuals—he even earned wages for his skillful work. One defining moment came through the historic dinner prepared for Jefferson and James Madison, a meal that famously aimed to preserve a fragile union. Hemings’ craftsmanship at the stove echoed loudly, especially in Philadelphia, where, in exchange for teaching his culinary expertise to his younger brother Peter, he negotiated and won his own freedom in 1796.

Freed from slavery yet bound by the weight of racial prejudice in America, James Hemings moved to cities like Philadelphia and Baltimore, determined to carve out his place in the world. Though surviving historical records are limited, it is clear Hemings navigated the tumultuous challenges faced by free Black people during those years.

Even after freedom, James wasn’t completely beyond Jefferson’s orbit. When Jefferson requested Hemings' culinary skills once more, James initially agreed, but soon found himself struggling with distrust and uncertainty. He boldly asked Jefferson about the precise terms of employment, demanding transparency, yet Jefferson did not respond. Despite the silence, Hemings briefly returned to Monticello, working there again for one short month—a poignant reminder of complicated relationships formed under the shadow of slavery.

James Hemings' life ended tragically in 1801, reportedly by his own hand under circumstances now concealed forever from history’s view. Yet, despite the tragedy of his passing and the injustices he endured, his enduring legacy persists. James Hemings dramatically reshaped the American culinary landscape, forever altering our nation’s palate with dishes that today we consider foundationally American: ice cream, macaroni and cheese, French fries, and crème brûlée.

Hemings' memory demands attention. His life reminds us of the resilience, creativity, and brilliance of Black folks in the midst of systemic cruelty. James Hemings’ legacy, born from pain but honed by an unyielding spirit, deserves a definitive place in our nation's historical consciousness.

Thank you for joining us today. For more engaging stories, visit One Mic History. Your continued support is greatly appreciated, we love you all.

-Countryboi

Beautifully written.