If you enjoy these Black History stories and want to keep discovering more, consider becoming a subscriber today. Your support helps me share these important narratives with even more people.

It’s a sweltering summer afternoon in 1949, Fairground Park Pool in St. Louis just opened its doors to Black swimmers for the first time. What should have been a joyful day quickly turned terrifying as thousands of angry white residents swarmed, wielding bricks, bats, and fists. When the dust settled, hundreds of police officers closed the facility, plunging the hopeful Black swimmers back into exclusion and fear.

Incidents like this aren’t isolated—they are entrenched in America's complicated racial history, especially around water. So, let’s dive deep into why Black folks have historically faced barriers not just access to pools and beaches, but to swimming itself.

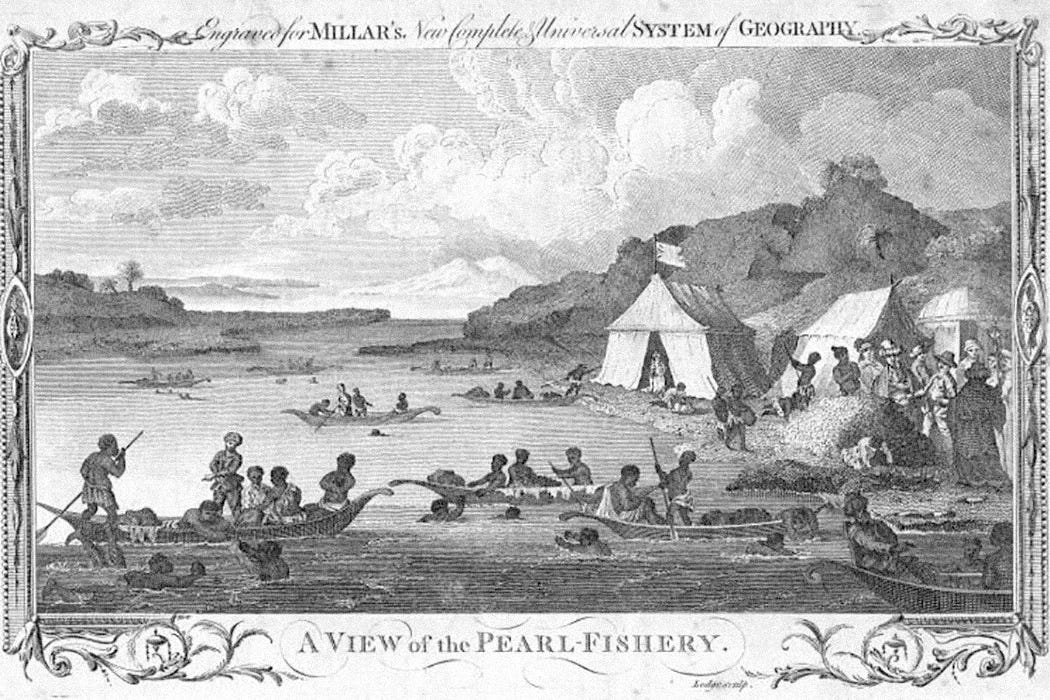

But first lets take a step back, Well before the slave trade ravaged Africa’s Western coastlines, swimming was fundamental across countless African cultures. Historian Kevin Dawson, in Enslaved Swimmers and Divers in the Atlantic World, documented Africans' exceptional swimming skills. Black folks along West Africa's coast and rivers mastered swimming for transportation, fishing, recreation, and survival long before Europeans arrived.

When Europeans encountered these skilled African swimmers, their abilities became tools of exploitation during enslavement. Enslaved Africans were forced into dangerous underwater tasks, salvaging wrecked ships or harvesting pearls. Black swimming proficiency was widely recognized, even envied among many Europeans who hadn't developed the same swimming traditions.

How did a our people become disproportionately disconnected from swimming?

This change began at the end of slavery. Post-Reconstruction and into the era of Jim Crow, racial segregation systematically stripped Black Americans of access to pools, beaches, and in turn swimming lessons, eroding what had once been a thriving swimming tradition.

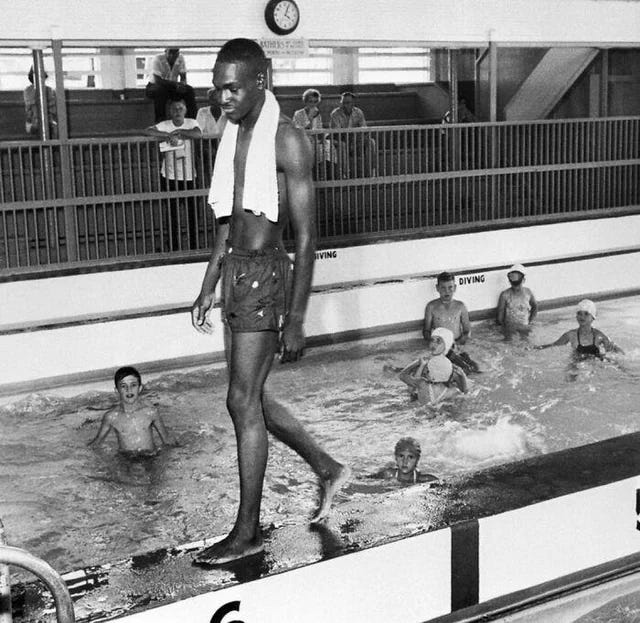

The early 20th century saw America invest heavily in public pools about 2,000 built nationwide. These spaces became social gathering points and symbols of community pride. But towns and cities predominantly restricted access to whites, especially in urban centers. When Black swimmers tried to exercise their rights and access public waters, violence frequently erupted, as seen in St. Louis in 1949 or famously in 1964 St. Augustine, Florida, where Martin Luther King Jr. famously protested segregation by integrating the Monson Motor Lodge motel pool only to see its manager furiously pour hydrochloric acid into the water.

Instead of integrating, many whites opted for "white flight," leaving public pools altogether for private, members-only swim clubs. Cities chose to close down their pools instead of integrating them, or secretly transitioned ownership to private clubs that maintained racial exclusivity under the cover of privatization.

Even when cities finally did build recreational pools for Black communities during the Civil Rights era, the facilities were often smaller, shallower, and inadequately funded. These pools weren’t built for real swimming, diving, or lessons, they were mostly splash pads and wading pools, underscoring a message: "Swimming is not for you."

This inequity was compounded by economics. Private clubs had membership fees, and for many Black households the costs were out of reach. Urban disinvestment and neglect meant public pools closed or deteriorated, furthering the racial gap in swimming exposure and training.

The legacy of exclusion and inaccessibility continues to impact Black communities. Researchers for USA Swimming reveal shocking realities: 64% of Black children possess limited or no swimming skills compared to only 40% of white children. The CDC reports Black youths aged 5 to 19 drown in swimming pools at rates over five times higher than white youths. These disparities aren’t random, they're rooted firmly in historical exclusion and lack of access.

Why do these disparities continue to exist?

A combination of historical lack of facilities, socioeconomic inequalities, generational fears (parents who themselves never learned to swim often raise children who perpetuate that fear), and even practical matters such as haircare concerns deters Black families.

Unlike the UK, where swimming education is part of the national curriculum, American swim instruction depends heavily on parental initiative and resources further amplifying the gap faced by underserved communities.

What can we do?

Fortunately today, some swimmers, educators, and advocates are stepping up to tackle the deep-rooted inequities head-on. National programs such as USA Swimming’s "Make A Splash" initiative and community groups like the YMCA have launched targeted efforts to provide low-cost and no-cost swimming lessons, water safety education, and pool access for underserved communities.

These initiatives aren’t just about swimming, they're about reclaiming what was unfairly lost. They're about survival, empowerment, and inclusion. Swimming isn’t a privilege; it’s a life skill. It’s safety. And it’s a part of our heritage we’re now working to reintroduce.

Water is powerful, lifegiving, and healing. Let's use it to bridge divides rather than deepen them. It's time not just to tread water, but to collectively swim toward a safer, more equitable future, one pool at a time.

What are you opinions on Black swimming, We'd love to hear your thoughts and ideas in the comments!

You can learn about more about Black History at my YouTube channel