If you enjoy these Black History stories and want to keep discovering more, consider becoming a subscriber today. Your support helps me share these important narratives with even more people.

On a blistering September day in 1919, a man found himself sprinting for his life. The sleepy town of Elaine, Arkansas had erupted into a nightmarish landscape for two whole days. Bodies of Black men and women lay strewn across the dirt roads, silent witnesses to unspeakable violence. Survivors hid in the cotton fields, their hearts pounding in sync with the distant gunfire.

Walter White, out of breath and fervently wishing for escape, ducked down a narrow alley. His feet pounded the ground, echoing the urgency in his chest, as he chased the salvation of the railroad tracks. He reached the train station just in time to hear the conductor’s final call for boarding. Relief washed over him until the conductor’s next words struck like needles.

the conductor remarked, “Why’re you leaving before the fun begins?” Without waiting for a reply, he added, “There’s a damned yellow nigger down here passing for white. When they get through with him, he won’t pass for white no more!”

What the conductor didn’t realize was that the passenger standing inches from him was the very man he was hoping to see strung up. White, his heart pounding in his chest, later wrote in his autobiography, A Man Called White,

“No matter what the distance, I shall never take as long a train ride as that one seemed to be.”

When the train screeched to a halt in New York, White’s colleagues at the NAACP enveloped him in the kind of relief that felt like coming up for air after nearly drowning.

A Man Called White

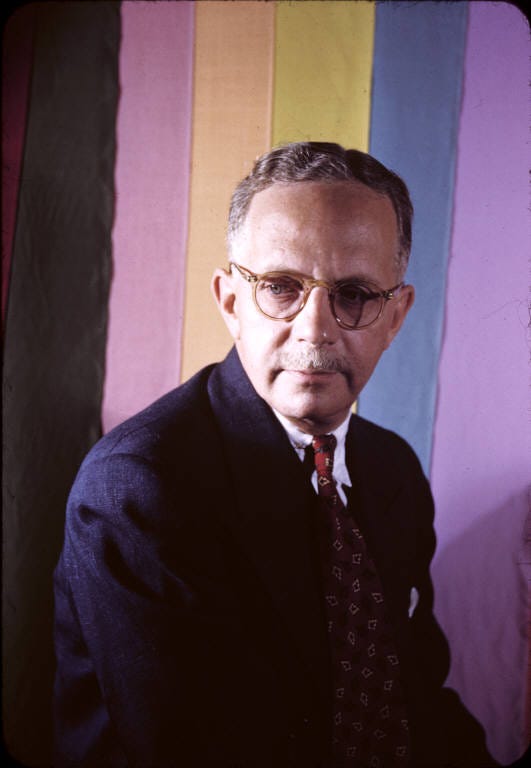

Walter White was born with blonde hair and piercing blue eyes on July 1, 1893, in the bustling heart of Atlanta, Georgia. At a glance, anyone would assume he was the epitome of Southern aristocracy. But beneath this deceptive exterior lay the soul of a man with a lineage as complex and tumultuous as the era he would grow up in.

Walter’s family tree was a tangled forest of enslaved African ancestors and white plantation owners. This fusion of races created a poignant reality for anyone born under the “one-drop rule,” a law that defined anyone with even a trace of Black ancestry was unequivocally Black. And within the aching chasm of this dichotomy, Walter White found not just his identity but also his life’s calling.

The White family, consisting of his mother Madeline Harrison and his father George White both former enslaved individuals who had clawed their way up to middle-class respectability as a teacher and a postal worker respectively.

In a world where Walter could have easily passed for white, he made a decision. He recounted the night that solidified his determination to stand against racial oppression in his memoir.

It was the harrowing night of September 22, 1906, that sealed young Walter’s fate. Atlanta was awash in flames of rage stoked by unsubstantiated claims that Black men had attacked white women. Driven by an illusory sense of supremacy, a white mob began a brutal massacre aimed at quelling the ascendant aspirations of Atlanta’s Black community. The mob headed to the Whites’ home, intent on terrorizing them. Inside, 13-year-old Walter stood resolutely with a shotgun in hand beside his father, his heart pounding with both fear and defiance. Miraculously, their home was spared, but the young boy’s outlook on life was forever altered.

After witnessing these atrocities firsthand, Walter resolved he could never align himself with a race that harbored such virulent hatred.

Graduating from Atlanta University in 1916, brimming with optimism and ambition, White embarked on a dual path as an executive at the esteemed Standard Life Insurance Company and as an unflagging participant in the civic landscape. That same year, he co-founded the Atlanta branch of the NAACP. Under his stewardship as secretary, the branch achieved a landmark triumph by preventing the school board from eliminating the seventh grade in a Black public schools.

Joining the NAACP

White caught the eye of two influential figures, NAACP founder W.E.B. Du Bois and Executive Secretary James Weldon Johnson. Impressed by White’s tenacity and political finesse, Johnson visited Atlanta in 1917. It didn’t take long for him to realize that this young man could be a powerful asset to the NAACP. By January 1918, White was whisked off to New York City, taking up the mantle of assistant secretary at the NAACP’s headquarters. Little did he know, he was about to walk straight into the storm.

America was grappling with an alarming surge of lynchings. Between 1889 and 1918, the NAACP had documented 3,224 brutal killings, with African Americans as the primary targets.

No sooner had White settled into his new role than he was dispatched to investigate a gruesome lynching in Estill Springs, Tennessee. The victim, an Black man named Jim McIlherron, had been accused of raping a white woman

a common and often unfounded accusation used to justify lynching.

Upon arriving in Estill Springs, White found the atmosphere thick with tension and hostility. He visited the scene where McIlherron’s lifeless body had been hung, the gruesomeness of the act still evident. He interviewed locals, including supposed eyewitnesses, who either reluctantly recounted the event or vehemently justified the lynching as an act of “justice.”

White’s presence was a risky endeavor; any suspicion of his true identity could result in his own death. This harrowing experience deeply affected him, strengthening his resolve to combat the horrors of racial violence. Through meticulous documentation and courageous commitment, White's investigation in Tennessee marked the beginning of a perilous yet pivotal journey neither he nor the NAACP had anticipated.

White’s mission was not just dangerous but with his fair complexion became both his sword and shield as he deftly assumed the identities of a white salesman or journalist to infiltrate these violent enclaves. Each investigation was like stepping onto a tightrope; a misjudged word or a crack in his disguise could mean death. One of his earliest assignments involved probing the hangings of ten men and the horrifying lynching of a pregnant Black woman.

In a chilling encounter, White faked friendship with a local merchant he suspected was involved in the killings. Remarkably, the merchant, mistaking White for a kindred spirit, began boasting about the lynchings, offering a firsthand account of the atrocities.

By October 1919 during the Red Summer, the searing heat of racial tensions boiled over in Elaine, Arkansas, where a lethal combination of labor conflict and racial hatred erupted. White vigilantes and federal troops massacred between 100 and 237 Black sharecroppers during a meeting on unionizing efforts. White was among the few who dared to uncover the grisly truths, meticulously documenting his findings in prominent publications like the Daily News, the Chicago Defender, and The Nation, as well as the NAACP’s own magazine, The Crisis.

His revelations were so explosive that the Arkansas Governor sought to ban the distribution of these publications, a testament to the power of White’s investigative prowess.

Amidst another lynching in Elaine, Arkansas, while staying at a local hotel, he noticed the sharp, suspicious eyes of some white townsfolk lingering on him longer than usual. The town had obtained a tip-off about a “troublesome white man” who was actually Black and working for the NAACP. While gathering information posing as a traveling salesman, his covert investigation almost came to a sudden end when a local law enforcement officer confronted him.

According to White’s own accounts, he narrowly escaped after being warned by a Black employee of the hotel where he was staying. This employee had overheard local officials discussing their suspicion of White and their plans to arrest him.

That night, White quietly fled the town under the cover of darkness, boarding the next train out. His colleagues in New York trembled with fear and relief in equal measure when White walked back into the NAACP office, very much alive.

“I Investigate Lynchings”

Over the next decade, White’s primary role was as an undercover investigator, a master of disguise who delved into the heart of racial violence. His luminous complexion and quick wits enabled him to coax confessions and anecdotes from those complicit in lynchings and riots, accounts that would later reverberate through the NAACP’s publications. His investigations spanned forty-one lynchings and eight race riots, each fraught with peril and narrow escapes from vigilante justice.

In January 1929, the world came face-to-face with an audacious truth-bearer. Walter White published a searing exposé in American Mercury titled “I Investigate Lynchings.” Later that year, his revelatory book, “Rope and Faggot: A Biography of Judge Lynch,” offered an authoritative and chilling analysis of lynching’s insidious causes. White wasn’t just documenting history; he was rewriting it, shaping the narrative of justice and human equality in America with every inked word.

White was a relentless advocate for federal anti-lynching legislation during his tenure with the NAACP. His surveys unveiled horrifying statistics, such as 46 of 50 lynchings in the first half of 1919 victimizing Black individuals. Partnering with the fearless Ida Wells-Barnett, White unmasked the root of racial violence—not baseless accusations of Black men’s rape of white women—but deep-seated prejudice and economic rivalry.

Amidst this turmoil, White’s efforts led to the Dyer Anti-Lynching Bill of 1922. The bill passed the House, only to be thwarted by the iron grip of Southern senators. Despite numerous attempts in the 1930s and 1940s, White’s legislative endeavors suffered similar disappointments, crushed by relentless Southern opposition.

Despite the setbacks, White’s perseverance raised public consciousness. His fight, however incomplete in his own era, catalyzed future civil rights victories. History finally vindicated White’s struggle in 2020 with the passage of the Emmett Till Anti-Lynching Act, a symbol of long-overdue justice.

Walter White remains an unsung architect of civil rights, whose strategic brilliance and unwavering commitment left an indelible mark on the trajectory of racial justice in America.

His story serves as a testament to complex racial dynamics that continue to shape America.

Thank you for joining us today. For more engaging stories, visit One Mic History and subscribe to our YouTube channel. Your continued support means the world to us. Enjoy our latest episode, and remember, we love you all!

-Countryboi

this kinda reminds me of Iola Leroy by by Frances Ellen Watkins Harper, at least the part about how confusing it was to be biracial in that time. This was also a very informative and moving piece so thank you for posting.